The story is disputed, as stories often are. And a song without lyrics…well, the story will rush in and, with the help of its listener, tell itself, and it will be both different and the same to everyone who hears it. It can’t be bothered with the facts.

Or, rather, it will take facts and make with them whatever it pleases. Stories want to be told, and heard, and passed along and told and sung and heard again, and they’ll do whatever they have to do to ensure that, seeking out those who have the craft and skill to get them out into the world and nagging away at them until they surrender, sit down, hammer it out, set it loose. And as often as not, even as they take a circuitous and often ‘unfactual’ path, even as we might never get back to the strict truths underlying their origins or inspiration, stories arrive, eventually, at something greater than the sum of their parts.

Here are some facts: Martha Ellis was a little girl who died of peritonitis, just shy of her 13th birthday, in 1836. She was buried at Rose Hill Cemetery in Macon, Georgia. Duane Allman was a young man, a founding member of the Allman Brothers Band, who died in a motorcycle accident in 1971, at the age of 24. He was buried at Rose Hill Cemetery in Macon, Georgia. The Allman Brothers’ best-known album, Eat A Peach, was released soon afterward and dedicated to his memory. Little Martha, a short instrumental piece that guitarist Leo Kottke has called “possibly the most perfect guitar song ever written,” was written by Allman and recorded for the album in October of 1971, only weeks before his death.

Duane Allman and his bandmates (one of them his brother, Gregg; another, bassist Berry Oakley, who would also die in a motorcycle accident not long after Duane did; he, too, is buried at Rose Hill), often wandered through Rose Hill Cemetery. What were they doing there? What a weird place to hang out. Because stories hate a vacuum, possible explanations rush in: it was a quiet place to think, compose, arrange, escape the crush of new fame, get wasted, be alone with a woman, any or all of the above. And maybe the dead exerted a pull on them they’d have been at a loss to explain: one of the band’s other best-known songs, In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed, written by guitarist Dickey Betts, also took its name from a woman buried at Rose Hill.

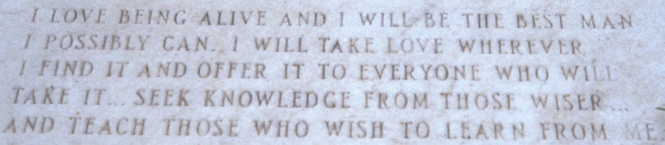

It’s an arresting image: a group of most likely scruffy, most likely stoned, assuredly brilliant young musicians stepping over the threshold between the ’60’s and 70’s, riding the first giddy wave of success (their first couple of albums had tanked but their most recent, the live release At Fillmore East, had put them on the map, and Eat a Peach would assure they remained there) wandering separately or together through a graveyard. They stop occasionally to kneel and squint at names carved into headstones: women’s names that maybe conjure melodies or lines of lyrics. A young man, fingers numb and calloused from constant playing, gazes up at a little stone girl, reads the poignant epitaph, and the notes come floating up, fingers to brain, brain back down to fingers by way of the heart and gut. Music has sprung from stranger sources.

Our Baby

She was love personified and her memory is a sweet solace by day,

and pleasant dreams by night to Mamma, Papa,

brothers and sisters. We will meet again

in the sweet bye and bye.

But the story is disputed, as stories often are. It is said that Betts and Allman insisted the songs ‘were named for one person, while actually being about someone else,’ written for, to, and about women with whom they were involved, women fortunate enough to have survived childhood, fortunate enough to still be living and in love with *musicians*. Duane is said to have nicknamed his girlfriend Martha, a riff on Martha Washington, because of the old-fashioned clothing she favored; Dickey Betts gave Elizabeth’s name to the woman he loved who had another boyfriend, one of Dickey’s closest friends, to protect everyone involved.

Okay; fair enough.

It is also said that Duane Allman claimed that he received Little Martha‘s melody whole in a dream, a gift from Jimi Hendrix. He visited Allman as he slept, plucked it out for him on a hotel bathroom sink-in that peculiar reality common to dreams where what is absurd is utterly ordinary-using the faucet as a fretboard. Hendrix had died only a year earlier, and it stands to some sort of reason that he might not have been finished making music yet, that visiting the dreams of another gifted musician was his way of passing that gift along, making sure the story didn’t end with him.

©Gered Mankowitz

Which of these stories is true? Which a lie? Is it maybe just a little too narratively perfect, a little too symmetrically sentimental, to find the song’s origins in a young man’s wistful gaze at the grave of a dead child, a man who would be sharing the ground with her only a short while later? Does the welter of conflicting accounts muddy up the picture a little, and is that a good or a bad thing, story- and life-wise? Some assert, others deny, and on and on it goes. Does that make the account more plausible, or less? Does the fact that Allman’s real ‘little Martha’, after his death, sued for control of his estate curdle the purity of the song that bears her name? Is it futile to try to square faulty reality with perfectly crafted art, or to make private creation publicly understood, to explain how and why we tell a story, sing a song, paint a picture? Maybe it was none of these stories; maybe it was all of them.

In the end, though, who cares? We have the song, and the song, once we’ve heard it, is ours to sing (or hear again and again in our heads, often to the point of distraction) in our turn. We can hear its melody any way we like. The dead speak amongst themselves, they speak to the living; the living speak to the dead and to one another. The story is the conversation, picked up and told and retold by those who follow. And we’re all trying to figure out the same thing.

A little girl died in 1836, of an illness easily treated today by the antibiotics that didn’t arrive on the scene until 1928 (the year my father was born), far too late to save her. My third son fell gravely ill with a similar illness in 2007; he was promptly cured and released from the hospital after the most harrowing week of his and his parents’ life. A young man who had only begun to express his brilliance (he and the band were best known for their skill at onstage improvisation, which often carried their live performances, to the delight of their fans, into wee hours that rang with extended instrumental solos) died after crashing his motorcycle, which he of course was driving too fast, into a lumber truck. He’d assumed he was more indestructible than anyone is, or maybe it’s only that death is something that no one, particularly a young man, can imagine. My middle son, at one time an ardent guitarist and with, on many occasions, a similar tendency to skate along the edges of profound risk, once texted me a YouTube video of one of the Allman Brothers’ epic performances, dazzled by their talent and endurance. I wish I could tell you that he was 24; the little shiver that might run through my reader is worth a lie or two. But he wasn’t. He was 16.

Did the fact that there are stories, and music, help me as I faced down horrible days when I feared I might lose my children? Maybe. I don’t know. But what else did I have?

Lorrie Moore once said, of the fact that we will all, someday, lose the people we love and with them their gifts and loving presence, ‘this is not acceptable. This is a design flaw.’ We are left to do with this what we can. So we tell stories with words and music and paintings and sculpture and film, and we visit others in their dreams, passing them along. It’s all we have. It’s the best we can do.

Duane Allman, November 20, 1946-October 29, 1971

©Melinda Rooney, 2017

Reblogged this on Recycled: Found Narratives of Everyday Life and commented:

R.I.P. Gregg Allman http://www.cnn.com/2017/05/27/entertainment/gregg-allman-obituary/

LikeLike