From the ‘Pop-up Poetry’ series of workshops sponsored by StoryStudio Chicago

(http://www.storystudiochicago.com)

Sunday, April 30, 2017

taught by C. Russell Price

(http://www.english.northwestern.edu/people/faculty/russell-price.html)

Each of Russell’s poetic exercises from the Pop-up Poetry series (and I really wish I hadn’t missed the first workshop) stands alone as a path to deeper creative fluency, but taken together they share a common intention: to startle the writer into thinking differently, to jump-start creative association and engagement with words and the world outside of us, to connect and communicate with the work and words of others. It’s a curriculum both of surprise-folding old and new together, forcing a new perspective that takes us out of ourselves-and recognition: there’s material everywhere. Sometimes we need to be reminded of that as we sit there with blank minds and pages.

This final class in the series examined several lesser-known poetic forms, daunting in their rigid structure and requirements. We were instructed to dive right in and make them our own.

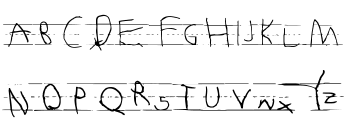

1. The Abecedarian

…an ancient poetic form guided by alphabetical order. Generally each line or stanza begins with the first letter of the alphabet and is followed by the successive letter, until the final letter is reached. The earliest examples are Semitic and often found in religious Hebrew poetry.

-The American Academy of Poets

Amy Ludwig VanDerwater

So we wrote our ABC’s down the left margin of a piece of paper, and had ten minutes to generate a poem: a love letter to a person, place or thing. Three imposed limits: the form itself, the time constraint, the theme.

I didn’t get real far. It was incredibly difficult.

After the divorce

Before the reunion

Coincidence? Or Fate?

David

Edged over

Found me at the table

God!

How weird!

I loved him when I was 20.

Yeeesh. And that was only the beginning of the alphabet. Imagine if I’d made it to K and Q and X. And Z. The idea that the structural requirements might actually enable rather than inhibit expression made sense to me in theory; in practice….well, yeah. Maybe I could look at it as an exercise, like a musician running scales.

Yeah. That’s it. I was just warming up. There was a big crowd on Sunday, 10 people all told, with only a short time to go over what we’d done, so it was hard for me to tell how many others had as tough a time as I did (and doesn’t it always seem like other people are ‘getting it’ more quickly than you are?).

2. Cento

From the Latin word for “patchwork,” the cento (or collage poem) is a poetic form made up of lines from poems by other poets. Though poets often borrow lines from other writers and mix them in with their own, a true cento is composed entirely of lines from other sources.

-The American Academy of Poets

Or, as Russell described it, it’s a sort of ‘chainmail’ made out of the pieces of other poems, ‘pulling a poem of your own out of the lines.’

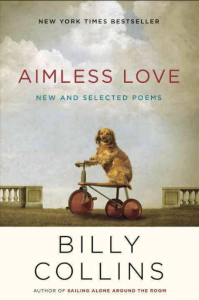

We were instructed to go to the poetry section of the store and choose a book, either by a favorite poet or one entirely unfamiliar to us. We were then directed to page through the poems, cherrypicking a striking line here, another striking line there, then assemble them into something resembling meaning.

Because my confidence was a little shaky I went straight for this, as he has never let me down:

We had ten minutes.

Cento

after Billy Collins

The tip of the nose seemed the first to be lost

If you tripped on a shoelace in the hall,

The air ionized as before a thunderstorm.

I heard the ghost-clink of the milk bottle

I fell in love with a wren

It played while I watered the plants

It repeated itself when I took a walk

There was a lot to notice that morning

My new copper-colored bicycle

The music of the spheres

I peered in at the lobsters.

How many things have I looked up

In a lifetime of looking things up?

It’s really sort of amazing what happens; it feels like the sense makes itself.

Again, there sadly wasn’t time to read them all aloud; we chose favorite passages and passed them around (this easily could’ve been a three hour workshop!).

3. Collaborative Poem

(*this is what I’m calling it; it may have a formal name that I don’t remember or know*)

It’s what it sounds like (remember the dread you felt in school when you were told to ‘pair off’ for some class exercise or other?): work with a partner, trading couplets back and forth: you write one, they write one, then you write one, etc. We were instructed to arrive at a theme by brainstorming with one another, then get down to writing. I don’t know if everyone was as squirmy about this as I was, but it seemed like it.

Why? Why did we feel that dread in school; why did we (or I, at any rate) feel this way?

I think one of the reasons I am a writer is that I am shy, am too easily distracted from my own thoughts by those of others, need to mull my words over and play with my ideas before I share them. It’s a comfortable if not always optimal place, and when you are asked to work with someone else (for some reason, it’s not as difficult for me with a group as with a single partner), you don’t have the safety of privacy anymore.

Or something.

Anyway. My partner Calvin (I never learned his last name…sorry, Calvin!) and I put our heads together. We were each skittish, I think (I know I was!), tossing the task back and forth like a hot potato. He said ‘you lead,’ and I balked, said something about being that dancer who prefers to follow (or not dance at all, unless I’ve had a couple of drinks), and we finally stumbled on Dancing as a theme.

Dancing Tango [a is one voice; b the other]

a

Let’s dance

Tango is cool with me

b

I’m not much of a dancer

More a stand-against-the-wall type

a

Come off that wall

Stand tall

You win

If you don’t fall

b

Well I guess I’ll win then

Which foot goes where?

a

Look what they

Doing, shakin

Soft shoeing

Let’s steal a dance

Do that prance

b

They move so fast

Like they know what they’re doing

Maybe if I move fast

I’ll look like that too

a

A one and a two

A stolen soft shoe

b

Who’s leading? The follower?

Or do I follow you?

While putting this post together, I came across this, a collection of poems for two voices:

4. Ghazal

Its restrictions belie an exhilarating freedom not found in other kinds of poetry. It becomes a liberating sort of puzzle.

http://ghazalpage.com

Pronounced ‘guzzle,’ this is a form I’d never heard of. Originating in Persia, its name originates in an Arabic root that means talking to women. At its best, flirtation is a subtle art, with a particular and often daunting set of rules. The ghazal is no different.

With gratitude to Holly Jensen at ghazalpage.com, here are the rules:

- A traditional or free ghazal has at least 5 end-stopped couplets. Repeat: no enjambment between couplets. A caesura or end-stop between the lines of couplets is common.

- Couplets are autonomous. They need not tell a single narrative, share a single voice, or use common imagery. You can even think of each couplet as its own small poem. They’ve been described as beads on a necklace: separate elements that combine to create a beautiful whole.

- The poet often refers to or addresses herself (or an alter ego/pen name) in the last couplet, directly or through word play.

[in addition to meeting the above guidelines, a ghazal in English has three additional rules]- The defining characteristics of a traditional ghazal are its rhyme and refrain. The refrain can be a word or phrase. The rhyme appears directly before the refrain. Every couplet ends with the rhyme and refrain. In the first couplet only, both lines end in the rhyme and refrain.

- Every line of the poem shares the same meter or syllable count.

- A ghazal doesn’t always follow every rule!

I found this ‘ghazal defining a ghazal’ to be (a little) more enlightening:

Ghazals on Ghazals

John Hollander

For couplets the ghazal is prime; at the end

Of each one’s a refrain like a chime: “at the end.”But in subsequent couplets throughout the whole poem,

It’s this second line only will rhyme at the endOne such a string of strange, unpronounceable fruits,

How fine the familiar old lime at the end!All our writing is silent, the dance of the hand,

So that what it comes down to’s all mime, at the end.Dust and ashes? How dainty and dry! We decay

To our messy primordial slime at the end.Two frail arms of your delicate form I pursue,

Inaccessible, vibrant, sublime at the end.You gathered all manner of flowers all day,

But your hands were most fragrant of thyme, at the end.There are so many sounds! A poem having one rhyme?

—A good life with sad, minor crime at the end.Each new couplet’s a different ascent: no great peak,

But a low hill quite easy to climb at the end.Two armed bandits: start out with a great wad of green

Thoughts, but you’re left with a dime at the end.Each assertion’s a knot which must shorten, alas.

This long-worded rope of which I’m at end.Now Qafia Radif has grown weary, like life,

At the same he’s been wasting his time at. THE END.

A string of beads: the ‘string’ is its series of repeated  rhymed refrains, its ‘beads’ the images: ‘wine, roses, candles, birds, war, prayer, politics, jokes, deathbeds, and kisses…’ [Holly Jensen, ghazal.com]

rhymed refrains, its ‘beads’ the images: ‘wine, roses, candles, birds, war, prayer, politics, jokes, deathbeds, and kisses…’ [Holly Jensen, ghazal.com]

I never quite found my footing with this one: *so many rules* with only a short amount of time left.

Clouds out the window, wool in a box

Ice in a plastic cup, handful of rocks

Seat back and tray table, cart in the aisle

Upright and locked, she says with a smile

You’re now free to move in the cabin…..

…aaaannnnd it peters out. Where’s that repeated phrase? Nowhere to be found. Why are those rhymes so lame? Best I could come up with. Not much came out on the page, but I was doing some real mental gymnastics; maybe that’ll help me the next time I take a stab at it.

What were the gymnastics, exactly? They were a struggle between the restrictions of form and the completely different restrictions of freedom. Russell mentioned hating the requirements of rhyme; it can shut down association and imagination…except when it doesn’t. They were a struggle between my own words and the words of others, an often noisy conversation, a jumble of sense and nonsense. It was a struggle between what hinders creative expression, and what enables it. It was a struggle between private and public, individual and communal, original and borrowed; it was a struggle with the self-contradictory idea that rules allow freedom, and that freedom creates rules, almost requires them.

Poetry is, I guess, a humanity-wide effort, a democratic art: we borrow from others, generate from within ourselves, join the conversation. We build it in cooperation with one another: everyone who came before us, everyone who will follow. It’s an alphabet, a patchwork, a dialogue, a string of beads, a dance. And when you’re jammed up, when you can’t quite complete that circuit between head and hand, mind and heart, ideas and images and words, ‘Steal everything!’ Russell said, then get out on the floor, write about dogs, and make something of your own.

Let’s dance

Tango is cool with me.

©Melinda Rooney, 2017

[Skeleton Tango by Laura-Anca Adascalitei]